The grim statistics, released daily, on the number of new coronavirus deaths in each country are pored over by the media and policy-makers as an indicator of when the pandemic might peak, whether lockdown is working, and whether more stringent restrictions might be needed.

The grim statistics, released daily, on the number of new coronavirus deaths in each country are pored over by the media and policy-makers as an indicator of when the pandemic might peak, whether lockdown is working, and whether more stringent restrictions might be needed.

Steve Proud and Sarah Smith provide insight into the current COVID-19 crisis.

Benjamin Franklin wrote that “in this world nothing can be said to be certain, except death and taxes.” However, the number of COVID-19 deaths is far from certain. In their book, The Tiger that Isn’t, Michael Blastland and Andrew Dilnot show that counting things in real life is seldom straightforward. “Numbers, pure and precise in abstract, lose precision in the real world. …. In maths they seem hard, pristine and bright, neatly defined around the edges. In life, we do better to think of something murkier and softer. It is the difference in one sense between diamonds and mushy peas.” Counting deaths is no different. The number of COVID-19 deaths is not an immutable fact to be uncovered but a statistical measure based on a certain methodology.

In this article we will look at what the estimates of COVID-19 deaths are measuring and discuss the different approaches (and assumptions) that are used. Knowing that these statistics are estimates does not make them less relevant to policy-makers but understanding the different approaches is important for getting a better insight into what is going on.

In principle this sounds like a straightforward question, but the answer is “it depends on who you ask….” There are (at least) four official statistics, two reported by the Department of Health and Social Care and two reported by the Office for National Statistics that take different approaches. There is also an estimate from the ONS that compares death rates with previous years. These are summarised in the table below. All the figures are for the number of people who had died by April 3rd – but they all tell a slightly different story.

| England & Wales | England | ||

| Daily notifications (Department of Health and Social Care, DHSC) |

Counts deaths by date of reporting Hospital deaths only People who have tested positive for COVID-19 |

4,093 | |

| Office for National Statistics Deaths registered | Counts deaths by date of registration

All deaths (including eg care homes) Death certificates that mention COVID-19 |

4,122 | 3,939 |

| NHS England (DHCS) | Counts deaths by date of occurrence

Hospitals only People who have tested positive for COVID-19 |

5,186 | |

| ONS Deaths occurred (and registered up to April 11th) | Counts deaths by date of occurrence

All deaths (including eg care homes) Death certificates that mention COVID-19 |

6,235 | 5,979 |

| Difference between ONS Deaths registered in 2020, and average of last five years | Comparable with ONS deaths registered | 6,082 |

Two numbers are published by the Department for Health and Social Care. These are the daily notifications (these are the headline numbers reported by the media each day) and the NHS England figure. The daily notifications capture deaths of people in hospital who have tested positive for COVID-19 that are reported on a given day. The higher NHS England figure counts COVID deaths the same way (i.e. deaths of people in hospital who have tested positive for COVID-19) but it does so by date of death (not date of reporting).

One advantage of the daily notifications is that the number can be published relatively quickly – the day’s reported deaths are reported the following day. As we show below, waiting for the NHS England figure for the actual deaths on a given day would result in a significant delay of several days.

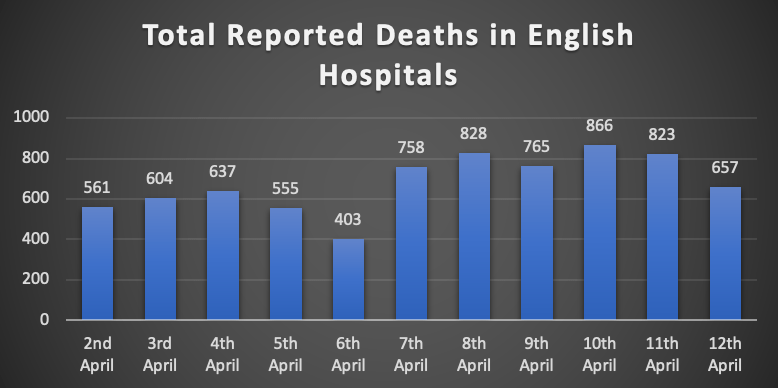

One potential issue with the number of reported deaths, however, is that reporting varies during the week. The daily notifications show regular falls in the number of deaths on Sundays and Mondays that reflect variation in reporting, not fewer deaths on these days. There is a tendency to jump on day-to-day variation (particularly when they show falls), but trends over several days will be much more reliable.

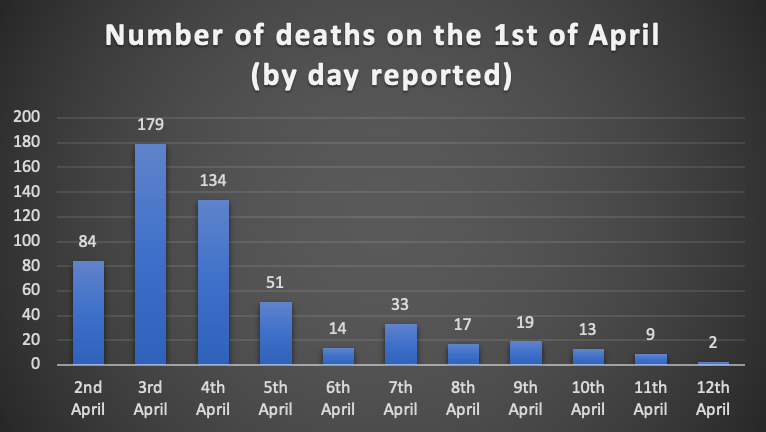

The number of actual deaths doesn’t suffer from this day-to-day reporting variation but there is a delay for the number of deaths on any day to be reported. On 1st April, 555 people who had tested positive for COVID-19 died in hospital but there was a delay of between one and eleven days before those deaths were reported. The deaths reported in the daily notifications on 12th April occurred between 26th March and 11th April. The headlines reported by the media (based on the daily notifications) are therefore telling a story about what has happened in the immediate past.

The ONS figures come from a different source, namely registrations of deaths (something which should be done within five days of a death occurring). As with the DHSC numbers, there are two figures for the number of deaths for a given day, one for the date the deaths occur and the other based on the date the deaths are registered.

The ONS figures are systematically higher than the DHSC figures for at least two reasons. The first is that they capture all COVID-19 deaths irrespective of where they occurred (including deaths in care homes for example), not just deaths in hospitals. According to ONS analysis, deaths in hospitals account for about 90% of the total.

The second reason is that the ONS figures take a broader approach to defining a COVID-19 death. The DHSC approach is to count only people who have tested positive for COVID-19. In the UK, however, there has not been widespread testing and it is mainly limited to people who are in hospital. The number of people tested understates the number of people who have COVID – the extent of this is very unclear. The ONS approach counts people where COVID-19 is mentioned on the death certificate. This includes people who have not tested positive for COVID-19 (eg because they have not been tested) but who are suspected of having the virus. This is broader than the test-based definition but is a subjective judgement and still may not really tell us who has died from COVID-19.

Both approaches – counting people who have tested positive for COVID-19 and counting people where COVID-19 is mentioned on the death certificate – are estimates of the true number of deaths that are due to COVID-19.

This true number is impossible to know with certainty. It is the number of people who have died as a result of the virus, who would otherwise not have died. This is impossible to count. For example, people with underlying health conditions are more likely to die when they test positive for COVID-19 compared to people with no underlying health conditions. What if people have terminal cancer and die with COVID-19. Should they count as COVID-19 deaths? In statistical terms, there are likely to be some false positives i.e. people who are counted as COVID-19 deaths because they tested positive, but who died from other causes.

Does this mean that the number of COVID-19 deaths is over-estimated? Almost certainly not. Just as there are false positives, there are also false negatives, i.e. people who do not count as COVID-19 deaths, because they were not tested and/or because COVID-19 was not mentioned on the death certificate, but who have died as a result of COVID-19. Such false negatives are more likely to occur when testing is low and when health services are overwhelmed such that people are not taken into hospital.

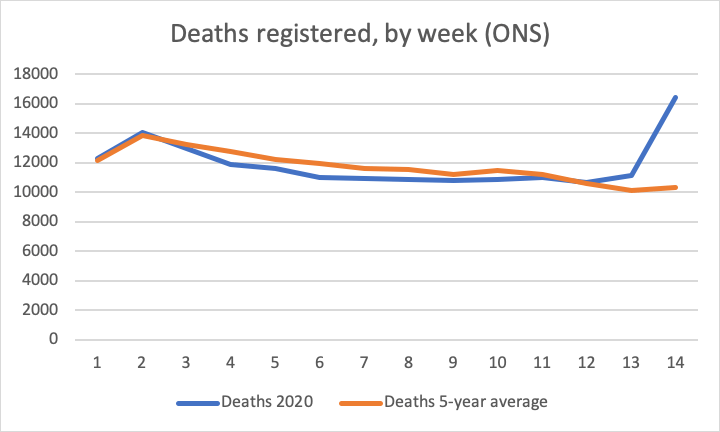

One way to estimate the true number of COVID-19 deaths is to compare the total number of deaths in this year (with COVID-19) with the total number of deaths over the same time period in previous years (without COVID-19). These figures are plotted in the figure. The ONS reported that the total number of deaths registered in England and Wales for the week up to April 3rd (16,387) is the highest in the twenty years they have been collecting the data and is 6,082 higher than the average for the same week over the previous five years. This is nearly 2,000 (more than 50%) more than the number of COVID-19 deaths based on death registrations that they reported for the same period. These figures point to the true number of deaths being much higher than any of the four official numbers, confirmed by recent reports suggesting many so-far unreported COVID-19 deaths in care homes.

This approach is not perfect. Factors that affect death rates (such as the weather) and factors that affect the timing of death registrations (such as when Easter falls) vary from year to year and affect the comparison (although taking an average over several previous years is more reliable than making a comparison with just the last year). The additional deaths may also not be the direct result of people catching the virus, but may be attributable to wider behavioural effects of the pandemic and the lockdown; for example, the increased pressure on the National Health Service that has seen other procedures are cancelled. However, the fact that there are 50% more deaths based on the year-on-year comparison than the comparable official number of registered deaths suggests that the number of false negatives (or hidden deaths) may be very large indeed. In the longer-term this comparative approach is likely to give the best estimate of the true number of deaths due to COVID19 and is a number to watch carefully on an ongoing basis.