Economics staff at Bristol University give their views on recent economics hot-topics. Where does the expert consensus lie?

Economics staff at Bristol University give their views on recent economics hot-topics. Where does the expert consensus lie?

By Ethan Lester

This month, we focus on three covid-related economic developments. Firstly, as Britain tentatively follows its ‘roadmap’ out of lockdown, we ask whether ‘zero-covid’ policies should be prioritised over ‘low-covid’ ones. Secondly, we ask if it was wise of Chancellor Sunak to announce a hike in corporation taxes two years in advance. Thirdly, we look at the long-term effects on the labour market of working at home during the pandemic. The format of this blog emulates the IGM panel of leading academic economists from the world’s top universities. It aims to locate the consensus among Bristol University staff on some of the main economic questions raised by current world affairs. As outlined in the series introduction, the format entails three questions to be answered on a scale of agreement (a ‘likert scale’), with the option to add a comment.

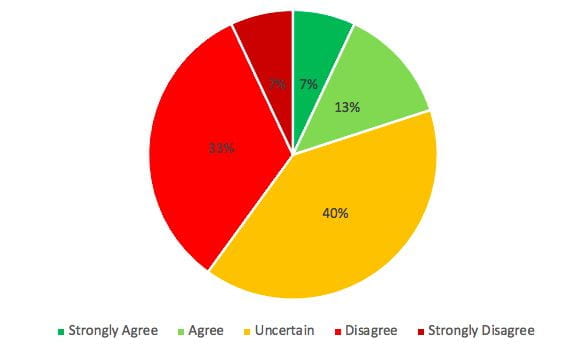

Question 1: ‘It makes more economic sense for governments to pursue ‘zero covid’ (elimination) lockdown policies rather than stop-and-go (mitigation) policies’. Do you agree?

Any comment on this question?

- Anonymous: I’m uncertain. I do not know the epidemiological models enough to discuss this (and to be frank, I do not think that any economists know them enough).

- Conrad Copeland: I strongly agree. This would have been an ideal first strategy, the short-term cost would have been higher, but the longer-term costs would not have been as severe. Its viability as a strategy now for governments that haven’t already pursued it is more questionable though with the right set of policies could be possible and desirable.

- Sekyu Choi: I disagree. Extreme policies are rarely optimal. What public health officials should be aiming at minimizing deaths and hospitalizations. However, it is not clear that you would like to drive those all the way to zero. Just think of traffic deaths or deaths by flu or deaths caused by alcohol consumption: what is the cost of reaching zero deaths from those? A similar question needs to be asked with respect to COVID.

- Anonymous: I’m uncertain. If it works, this is probably true. However, how well a zero covid strategy works depends on many factors outside the control of the government (e.g. geography, behaviour of neighbouring countries etc.).

- Sarah Smith: I agree. The benefit of an elimination policy is that it reduces uncertainty in the long run and this has huge economic benefits (although I am not sure whether complete elimination is either possible or socially desirable).

- Hans Sievertsen: I’m uncertain. I agree if we could guarantee that after a period of strict lockdown we would return to “normal” without any risk of new lockdowns. But I don’t think anyone can guarantee that.

- Anonymous: I strongly disagree. The only country in the world that has adopted this policy successfully is China and we are not China.

Verdict: Few respondents (20%) agreed or strongly agreed with this statement, and those who did were only likely to do so hypothetically. ‘Uncertain’ was the largest camp, with 40% of respondents feeling this way. To some uncertain economists, it is not yet clear what kind of picture is painted by the data (or, the data is not easily accessible). Other uncertain economists believe ‘elimination’ policies only work if there is a high level of international cooperation, among other factors which are difficult to control for. A notable proportion of respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed (40%). One such economist notes that ‘elimination’ policies have only worked for certain countries. Another believes that pursuing zero-covid deaths is socially undesirable, otherwise governments would have to commit to, for example, zero-alcohol deaths. As a reminder of just how polarising questions like these can be, an equal proportion of respondents ‘strongly disagreed’ as ‘strongly agreed’.

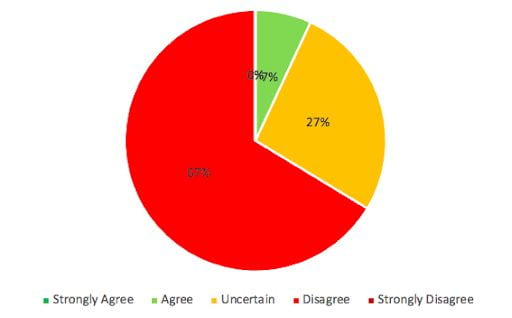

Question 2: UK corporation tax rates are set to rise in 2023. Given the constantly changing economic circumstances, do you agree that it is unwise to announce a tax so far in advance of its implementation?

Any comment on this question?

- Anonymous: I disagree. Only in very special circumstances surprises are good economic policy. People would argue that by surprising corporations you could be able to collect more taxes initially but I think that it could generate more problems than anything else as exit always occurs in the margin: only firms that are bearly economically profitable (in the sense that they can do better somewhere else) will be affected, so these companies may collapse once they are surprised if you do not let them plan. There are other issues if you try to keep a secret and it leaks. On the other hand, lobbying and political pressure could intensify and the net effect until 2023 implementation could be a wash.

- Anonymous: I’m uncertain. It is a very complicated question which relates to issues of commitment, uncertainty, behavioral responses etc. In short, announcing early gives commitment, but gives time for people to react, with possibly detrimental effects.

- Anonymous: I disagree. Corporation tax in the UK, even after the change will remain historically low, and internationally competitive. By pre-announcing, however, it seems apparent that it is designed to deliver political capital, particularly if the economy rebounds sufficiently to allow the policy to be ameliorated.

- Hakki Yazici: I disagree. There are both benefits and costs of announcing a policy in advance. A key benefit is that you are giving economic agents time to prepare themselves for the policy change. A possible cost is that when the time arrives and the policy is put into effect it may not fit the needs of the economy at that moment. For certain types of policies, such as monetary policy, it is really crucial that the policy is fine tuned to the short-term needs of the economy and committing to a policy in advance may be really costly. However, the behaviour that corporate taxes affect, mainly capital investment, is not such a short-term behaviour as firms cannot adjust their capital stocks very quickly. As such, corporate taxation is not one of those policies that require a lot of flexibility in the short run. Because of this, I think the benefit of announcing corporate tax policy two years in advance is likely to outweigh its costs.

- Conrad Copeland: I disagree. If we accept that it is a credible commitment on the part of the government, it allows for enough time through the uncertainty for businesses to plan and prepare. The current uncertainty arguably makes the necessary lead-time longer.

Verdict: Just over 2 in 3 economists disagreed with this statement. A recurring theme was that businesses should be given preparation time upon announcement of a tax rise. However, there were no ‘strongly disagree’ responses, and those who disagreed were likely to mention that there are also disadvantages to announcing a corporation tax rise so far in advance. Potentially owing to the complicated nature of the question, 27% of economists were uncertain. Some of the most detailed responses seen so far in this blog series were given to this question: perhaps the economists were particularly well-informed on (or just passionate about) this topic. Of those economists who agreed with the statement (7%), none offered any comment.

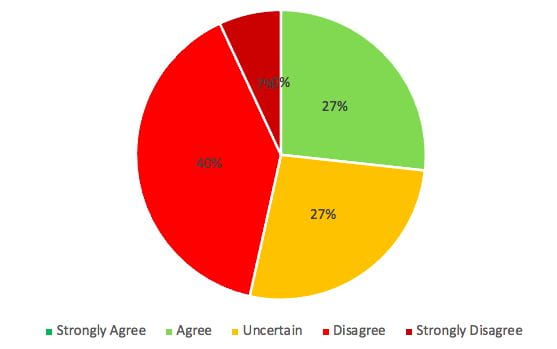

Question 3: Would you agree with the view that working from home is ‘revolutionising’ the labour market?

Any comment on this question?

- Edmund Cannon: I agree. Many individuals will find it easier to work from home. Whether a return to the putting out system (widely used up until the eighteenth century and even nineteenth century) can be described as revolutionary is a semantic issue. I suppose for economists who do not know any economic history the return to a system used for many centuries will appear new and novel.

- Anonymous: I agree. Working from home will reduce one of the worst human activities: commuting (this has been tested…it is bad)…It will also allow for more connection between the different parts of the world: all those night owls will be more productive and will be able to work in different parts of the world.

- Anonymous: I disagree. I think that the pandemic has fostered investment in better technologies. However, people were working in the office before and this reflected preferences (maybe not workers’ preferences but at least the agreement struck with their employers). For this reason, I would expect working from home to be far less of a trend than currently discussed. That being said, before the pandemic, there were discussions about the working time during the week, as well as the supply of services across borders.

- Anonymous: I strongly disagree. In the long term, if firms embrace WFH, the biggest impacts are likely to be on housing markets, and opening up the labour market, without geographic requirements. However, the market power is really held by firms, rather than individuals. Conrad Copeland: I’m uncertain. The impact of working from home will depend on the post-pandemic outcome and particularly whether employers try to enforce a return to the office/workplace and to what extent workers resist this pressure.

- Anonymous: I disagree. Working-from-home is only really feasible for a subset of jobs (although this share is increasing as digitisation progresses).

- Sarah Smith: I agree. I interpret this question to mean that the work-from-home covid experience has fundamentally changed firms’ and employers’ view on the possibilites of working from home (with all sorts of implications for city centres, housing markets, city centres, retail) but we haven’t yet seen the death of the office.

- Hans Sievertsen: I disagree. I guess some employers have realised the benefits of working from home, or at least seen that it might work better than expected. It will probably increase flexibility, but I would not call it a revolution.

Verdict: Just under half of the respondents disagreed or strongly disagreed with this statement. Two of the economists who replied this way note how firms do not prefer when their employees work from home, and firms generally hold more bargaining power than employees. Other economists add how a ‘revolution’ has only been experienced in certain industries, or by those who don’t have children. Of course, it also remains to be seen which trends will remain after the pandemic. Perhaps this is why 27% of the economists replied: ‘uncertain’. The same proportion of economists agreed, although none went so far as to pronounce ‘the death of the office’. There is no clear consensus on this question, given the many different interpretations of the word ‘revolution’.

Final thoughts This survey aimed to find the expert consensus on three topical economic questions. On whether or not ‘elimination’ lockdown policies are more economically desirable than ‘mitigation’ ones, the consensus was that the ‘elimination’ method is only preferable in hindsight, or under certain circumstances. On the announcement of a rise in corporation tax, opinion was mostly in favour of there being a two-year window between the tax’s announcement and its implementation.

Finally, opinion was split on whether working from home represents a ‘revolution’ in the labour market.

What would you like to Ask the Experts? Send an email to Ethan at xn19143@bristol.ac.uk with your suggestions for future questions on this blog.