Staff at the University of Bristol’s School of Economics give their views on the UK’s new trade agreement with the EU. Where does the expert consensus lie? Undergraduate student, Ethan Lester summarises the results.

Staff at the University of Bristol’s School of Economics give their views on the UK’s new trade agreement with the EU. Where does the expert consensus lie? Undergraduate student, Ethan Lester summarises the results.

After years of negotiations, the UK has finally reached and ratified a Brexit agreement with the EU. Both sides claim the deal protects their cherished goals. Britain said it gives the UK control over its money, borders, laws and fishing grounds and ensures the country is “no longer in the lunar pull of the EU.” Ursula Von der Leyen said it protects the EU’s single market and contains safeguards to ensure Britain does not unfairly undercut the bloc’s standards.

What do the experts think? The devil is in the detail of the 2000-page agreement, but three of the more contentious questions pertaining to the Brexit deal have been chosen for the analysis of Bristol University’s economists.

The format of this blog emulates the IGM panel of leading academic economists from the world’s top universities. It aims to locate the consensus among Bristol University staff on some of the main economic questions raised by current world affairs. As outlined in the series introduction, the format entails three questions to be answered on a scale of agreement (a ‘likert scale’), with the option to add a comment.

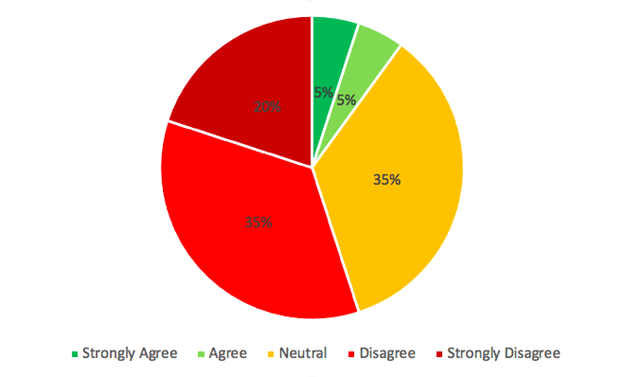

Question 1: “It is good for Britain’s economy that the Brexit deal allows freedom from EU product, environmental, and labour rules”. Do you agree?

20 responses

Any comment on this question?

Anonymous: I’m neutral. It depends on what the deviations would be. The different rules are designed/optimised as a way to protect producers and consumers in the EU; the UK is quite similar to the EU in many aspects. In short, the main incentive to deviate would be to be a hub in order to produce cheaper products/services for the EU but then the deal would impose tariffs and the rules of origin would markedly limit the advantages of doing so. In short: very unclear advantages at this stage.

Edmund Cannon: I disagree. Freedom from the EU’s product, environmental and labour rules is only valuable if we are going to diverge significantly. If deviating from the EU’s rules results in lower standards, then it may conceivably improve measured GDP but at the expense of making most people worse off.

Sarah Smith: I’m neutral. Regulation can be costly – so removing it should help the economy in a narrow sense. But the effect on welfare of removing welfare may be negative.

Peter Spittal: I’m neutral. The answer depends on politics and political economy: will the UK choose to implement “better” or “worse” rules on e.g. goods taxes and employment relations? In the short term I expect little to change, and in the longer term it’s too hard to tell (who will be in government in 5 years?)

Christine Valente: I disagree. In the short run, some British businesses may benefit from lower costs due to not being subject to these regulations. But in a broader and longer-term sense, either the UK will choose high standards for all of these aspects and therefore not differ much from EU rules, or choose low standards to undercut the EU, with negative long-term consequences.

Pawel Doligalski: I disagree. I believe now British bureaucrats will need to do the work in setting these rules that French, German and so bureaucrats used to do on their behalf. Furthermore, if there will be any discrepancy in rules between the UK and EU, it will make trade much more difficult.

Ahmed Pirzada: I disagree. The 21st century challenges need more and more of international cooperation. The socio-economic challenges which had emerged as a result of globalisation, automation etc should have been dealt with an upskilling of the labour force and redistributive policies.

Verdict: The majority of respondents (55%) at least slightly disagreed with this question. Justifications varied – some respondents discussed how difficult international cooperation can be without a mutual regulatory framework, others stress the trade-off between looser regulation and economic welfare. The 10% of ‘agree’ or ‘strongly disagree’ respondents provided no comment to back up their views. 35% of respondents were ‘neutral’ because they were unsure if the UK plans on pursuing its own completely distinct set of standards, rather than keeping or slightly modifying existing EU ones.

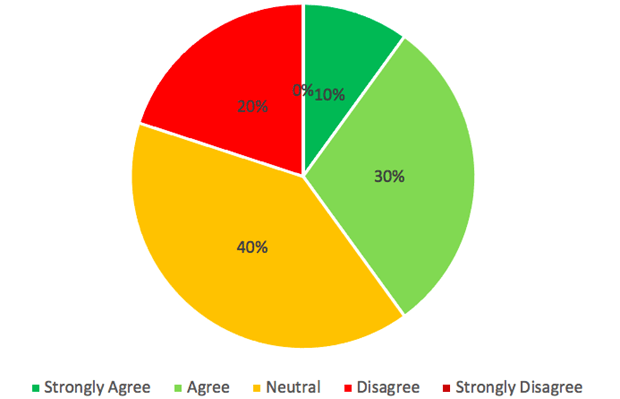

Question 2: “Brexit marks the beginning of the end of the City of London’s dominant position as a financial centre.” Do you agree?

20 responses

Any comment on this question?

Anonymous: I’m neutral. It depends a bit on the coordination of the different actors. There are local spillovers leading to possible multiple equilibria. The most likely outcome is that the City will lose a bit to Frankfurt and New York, but not massively in the short run.

Edmund Cannon: I disagree. It is far too soon to say that the City will decline.

Sarah Smith: I agree. We have already seen jobs in finance move to other European countries and the trend is likely to continue. The deal had less focus on services, creating a lot of uncertainty.

Christine Valente: I’m neutral. The City’s position was not a priority for the UK government in the negotiations of the trade deal, and will suffer from it. However my understanding is that there is not yet any clear indication of much activity being relocated.

Conrad Copeland: I disagree. Brexit and its fallout will cause some movement towards other centres (as we’ve started to see already) but predictions of the collapse of London as a global financial centre are premature, there is a lot of path-dependency involved. That being said, I think there is a major opportunity for Dublin to move up as the anglophone gateway to the EU.

Ahmed Pirzada: I disagree. It will take much more to undo London’s dominant position. Obviously, I am assuming that the government will be able to work out a mutually beneficial arrangement with the EU when it comes to trade in financial services.

Verdict: There was no clear consensus on this question. There was some divide between those who believed it was too soon to know what will happen to the UK’s financial sector post-Brexit, and those who did not. This uncertainty produced a relatively high response rate for ‘neutral’ – 40%. Some of the 40% of respondents who agreed or strongly agreed pointed to how the center of gravity has already shifted towards other European financial powerhouses. Some of the 20% who disagreed were certain that the worst of the damage from Brexit has already been inflicted on financial services; or, they were optimistic about a future financial services deal.

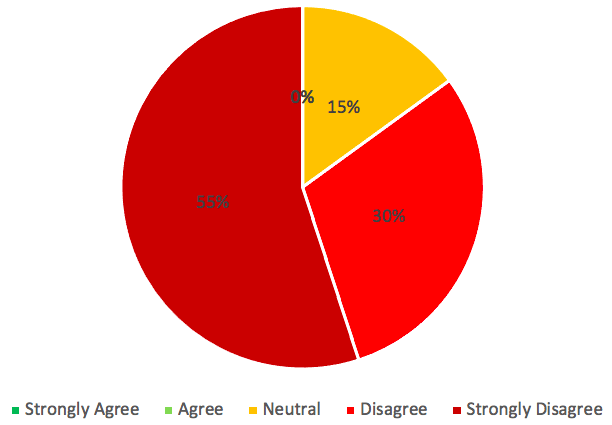

Question 3: Boris Johnson called the Erasmus Programme an ‘extremely expensive scheme’. Do you agree with the UK’s withdrawal from it?

20 responses

Any comment on this question?

Edmund Cannon: I strongly disagree. As an alumnus of the Erasmus scheme, I am against the UK’s withdrawal. Involvement in Erasmus gave the UK “soft power” as visiting students return home knowing more about the UK: it is difficult to know whether this soft power was expensive or not (how to compare the cost of Erasmus to the cost of two aircraft carriers that we possibly cannot use?).

Anonymous: I strongly disagree. Less expensive than giving money to your pals.

Sarah Smith: I strongly disagree. Britain’s universities – and its students – have benefitted enormously from international mobility under the Erasmus programme. Participation in the scheme has also been shown to increase international labour market mobility. To say that the scheme is expensive is narrow and short-sighted and ignores the huge benefits that it brought.

Pawel Doligalski: I disagree. I believe that the Erasmus Program is one of the most important policies that help cultivate an European identity (next to their own national identity) among young people. I disagree it is a good idea to withdraw from it, but of course that’s consistent with the overall course taken by Boris Johnson.

Hans Sievertsen: I disagree. It is not very helpful to talk about how expensive this programme is without any serious effort of quantifying the benefits. The latter is very challenging, I admit.

Anonymous: I’m neutral. I don’t know enough about how expensive it is, unfortunately

Anonymous: I’m neutral. I do not know much about the costs or benefits of the Erasmus programme.

Verdict: Respondents were resoundingly negative about the UK’s withdrawal from the Erasmus student exchange scheme. Of 20 respondents, zero agreed or strongly agreed. Still, those who disagreed or strongly disagreed admit that it is hard to quantify the economic benefits of Erasmus. This might be because Erasmus is more of a social policy than an economic one. Perhaps the fact that some of the respondents have directly benefited from the scheme caused a degree of bias. Neutral respondents were more related to Boris Johnson’s comment on the price of Erasmus, rather than his decision to withdraw from it. One stray respondent was chagrined at Mr Johnson’s hypocrisy in calling this scheme expensive yet being fiscally wasteful elsewhere.

Final thoughts: a good deal?

This survey aimed to find the expert consensus on how the Brexit deal affects regulation, financial services, and Erasmus exchange students. The answers were polarised on the regulatory implications of Brexit, were more nuanced on the future of the UK’s financial sector, and were more unified on the question of Erasmus. Though the reception to these three specific aspects of the deal were generally negative, we cannot extrapolate that they find the Brexit deal negative on the whole. Nor can we extrapolate that they found the Brexit deal better than any alternative (no deal or no Brexit).

Notably, there remains a large amount of uncertainty over the long-term effects of Brexit. If the trade agreement was meant to provide assurance over the post-Brexit economic outlook, the responses of this survey suggest otherwise. Also, it is easy to forget that our experts might have personal attachment to particular economic policies, and that their answers may be skewed accordingly. This fact serves as a reminder of just how much economic policy affects our lives.