The coronavirus pandemic has seen a rapid and marked shift in the balance between markets and government.

The coronavirus pandemic has seen a rapid and marked shift in the balance between markets and government.

Professor Sarah Smith explores governments responses to the current COVID-19 crisis.

Governments around the world have responded to the crisis with massive spending commitments. In the UK, the Conservative Government overturned a decade of austerity budgets and announced an estimated £60 billion of spending (including more generous income support and unemployment benefits, business support and increased NHS spending ) an equivalent to 3 per cent of GDP, as well as a further £360 billion worth of guarantees for firms taking loans and deferrals of tax payments.

Governments have also seen a huge increase in their powers in recent weeks. Emergency legislation has given the UK government emergency powers for two years, including the power to restrict gatherings, close premises and to detain people on “public health grounds”. This marks a severe curtailment of important civil liberties, including the freedom to travel and the freedom to assemble. In the UK, the powers will be reviewed every six months. In Hungary, the parliament approved a bill to allow Prime Minister Viktor Orban to rule by decree. The bill includes harsh penalties of up to five years in prison for spreading anything the government deems “fake news”. No elections can take place while the measures are in effect and the bill does not include an end date.

These responses to the pandemic measures highlight the unique role played by governments in a modern economy. This article asks what governments do and why are they so important in a time of crisis?

What do governments do?

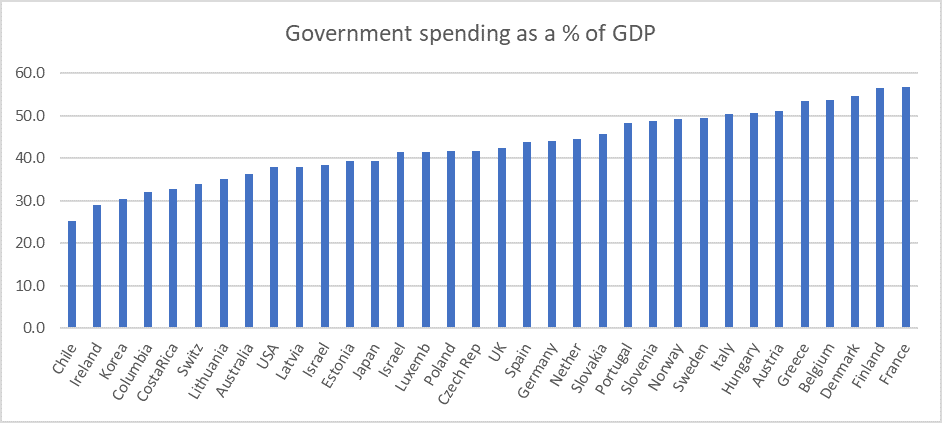

The chart below shows the share of GDP spent by the government for all OECD countries. There is wide variation – at the top of the distribution, government spending in France accounts for more than 55 per cent of GDP, while at the bottom, in Chile, it is 25 per cent of GDP. However, even in countries where the government is relatively small, it is still the single, dominant economic actor in the economy. The UK sits in the middle of the distribution. In 2015 (the year for which these OECD figures are available) government spending was 42.3 per cent of GDP and it fell to less than 40 per cent by 2019. The spending measures announced in response to the pandemic will see this figure rise substantially.

Source: OECD (figures from 2015)

What do governments spend all this money on? Governments are unique among the different actors in an economy in having coercive powers – they use those powers to maintain order and to regulate activities and also to collect taxes that can be used to fund public services and benefits (pensions, income support, unemployment benefit). Differences in government spending across countries typically represent variation in the extent to which governments intervene in and regulate the economy, fund public services and distribute benefits (pensions, unemployment benefits and income support).

“If capitalism is so great, why does it need to be bailed out by socialism every ten years?”

Economic arguments for government action often focus on cases of market failure – i.e. cases where unregulated markets fail to deliver good outcomes. For example, firms might exploit market power to charge excessive prices, and this creates a case for governments to break up monopolies.

Externalities are a major source of market failure. These are the positive and negative effects of agents’ actions on others that agents do not fully take account of when deciding how to act. Pollution is a classic case of a negative externality – when I decide to drive, I probably think about the private costs and benefits of driving and not about the damage it does to air quality. Without government intervention, there will be too much of any activity that creates negative externalities. Hence governments intervene and use regulation or taxes to reduce the level of the activity.

Social distancing is an action with a positive externality. If each person stays away from others they reduce their own risk of getting infected but they also reduce the risk of infecting others – in other words, they generate a positive externality. Without government intervention, some people will voluntarily internalise this externality and keep their social distance, but not everyone will. Governments can use their coercive force to ensure that people achieve the best outcome collectively by ensuring that (almost) everyone keeps their social distance.

Governments are also better than markets at stabilising the economy and in minimising the economic damage done by an external shock such as the coronavirus. Governments are much better placed than other economic actors to deal with aggregate shocks that hit large parts of the economy. If people have private unemployment insurance, a private insurer might not be able to pay out if lots of unemployed people make a claim at once. Governments have a much greater capacity to make payments – not because they would want to use their coercive powers to increase taxes now (which would further reduce aggregate demand) but because they can easily borrow money because lenders know that, as a result of their coercive taxation power, they will be able to pay back in the future. Governments are less likely than any individual economic actor to go bust. And borrowing money to provide unemployment benefits – such as the recently announced earnings replacement for employed and self-employed workers – helps households to maintain spending – which in turn reduces the aggregate effects of increased unemployment and helps to prevent even more people losing their jobs.

Crises can be good for governments

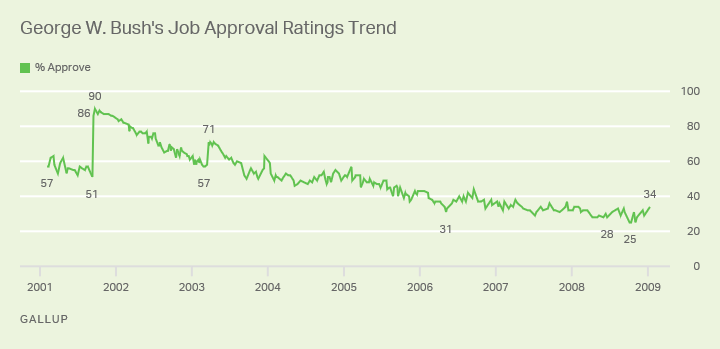

In times of crisis, people look to governments because they are the only actor with the power to take the necessary actions. A crisis can be personally very good for a political leader’s approval rating. Boris Johnson has seen his net personal rating (the difference between the percentage that view him favourably and the percentage that view him unfavourably) improve from -3 (43 per cent viewing him favourably, 46 per cent unfavourably) in the first half of March to +20 by the end of the month (55 per cent favourable; 35 per cent unfavourable), his highest rating by some distance since becoming leader. Over a similar period, Donald Trump’s approval rating (the percentage who approve of what he is doing) has increased from 42 per cent to 46 per cent, his highest rating since the inauguration. However, before feeling too cheerful, Johnson and Trump may want to look at what happened to George Bush who saw his approval rating spike up in the aftermath of the 9/11 attacks, only to decline steadily down over the years that followed. Concern over the lack of personal protective equipment for NHS staff and low levels of testing suggests that Johnson’s crisis popularity boost may be similarly short-lived.

Dealing effectively with crises can have a permanent positive effect on how the public perceives the government. Researchers studying the effects of the Ebola epidemic in the West African countries of Guinea, Liberia and Sierra Leone in 2014-15 found that exposure to the disease had a positive effect on the public’s trust in the state. Areas with high exposure had a more positive view of the legitimacy of the state after the epidemic than before (and compared to low-exposure regions). The changes in perceptions also had a direct political impact. In the post-epidemic presidential elections, the share of the vote for the incumbent party disproportionately increased in regions that experienced a more intense transmission of the disease. By reacting effectively to emergencies, governments can increase the level of trust among citizens in a short period of time. In the context of less developed countries, this can be particularly important: Work by economists Daron Acemoglu, Simon Johnson, and James Robinson has shown that good government is good for the economy in the long-run and that strong institutions are fundamental for long-term economic growth.

These studies suggest that governments can use their unique powers in a time of crisis to strengthen their positions and increase their legitimacy, with positive long-term effects. However, the situation in Hungary points to a potentially more sinister end. The fact that governments require extraordinary powers to compel compliance creates a dilemma. For the government to be a successful problem-solver, it must also be powerful enough to potentially be a problem itself. There are many examples from history that show that governments can abuse their monopoly of power just as much as firms. Whatever happens, the current pandemic may have lasting consequences for the role of government in many economies.