Economics staff at Bristol University give their views on recent economic developments. Where does the expert consensus lie?

Economics staff at Bristol University give their views on recent economic developments. Where does the expert consensus lie?

By Ethan Lester

The battle against inflation is fueling uncertainty in a crisis-weary global economy. Financial markets are scrambling to keep apace as most central banks continue on a monetary tightening course.

The vulnerability of large economies to any additional shock was starkly demonstrated last week, as news of a government plan for tax cuts and borrowing set off turmoil in the UK bond market and plunged the pound to historic lows. Banks do not like such uncertainty, so they may respond by ratcheting rates on their mortgage products above the record highs they are already at.

These themes charge my first two questions in this month’s survey of Bristol economists. Firstly, I am interested in gauging the expert opinion on Britain’s economic growth outlook, given that GDP shrank by 0.3% last month. Secondly, I would like to know why, against a perfect storm of rate rises and a cost of living crisis, UK house sellers are continuing to raise their asking prices.

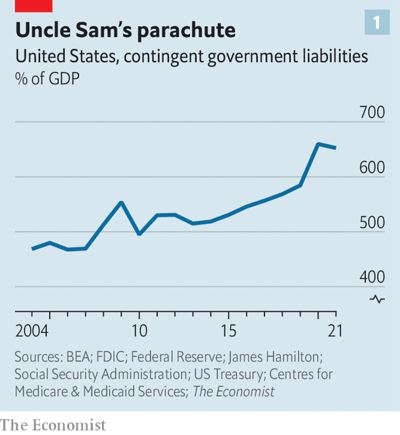

For my third question, I turn to America’s public debt. Consider the figure below, which shows the estimated size of America’s ‘bail-out state’. The Economist has combined US federal public debt with off-balance-sheet obligations (like healthcare payouts and mortgage guarantees), and found that the state now has liabilities worth more than six times the country’s GDP. I want to know if our economists find this data a cause for concern.

For those unfamiliar, this blog follows the format of the IGM expert panel on vital policy issues. The three questions will be answered on a scale of agreement (a ‘likert scale’), with the option to add a comment.

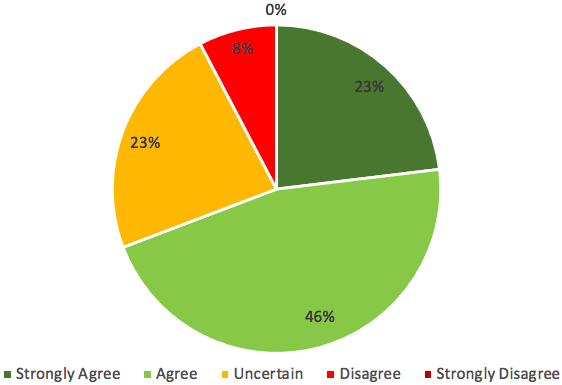

Question 1: The Bank of England has warned the UK may already be in a recession. Do you agree?

Any comment on this question?

Anonymous: I strongly agree. Recession has a technical definition, but the UK is clearly on track for a period of stagnation, if not a serious crisis. Reasons: high deficit, large inequalities, failing public services, low appetite for redistribution, Brexit. Also: incompetent politicians.

Anonymous: I agree. Way too much is made in economic commentary of investment and exports when talking about GDP and recessions. These things are of course really important, but if you want to understand why a recession is likely, go back to your GDP accounting. Household consumption is the largest slice of the pie, and that has been hit hard by energy prices and, now, sharp interest rate rises (so mortgage costs go up). This is enough to drive a recession whatever even if, for example, exports rise due to the depreciation.

Verdict: Just over two thirds of the responding economists either agree or strongly agree that Britain is already in recession. Interestingly, one economist disagrees with the Office for National Statistics over how far industrial output is causing negative growth. This respondent names lower consumption as the ‘x-factor’, whereas another economist focuses on the intersection of socio-economics, geopolitics, and domestic politics. Almost a quarter of respondents are uncertain on this question and one lone economist takes a dissenting view. One can only speculate their reasons because they offer no comment.

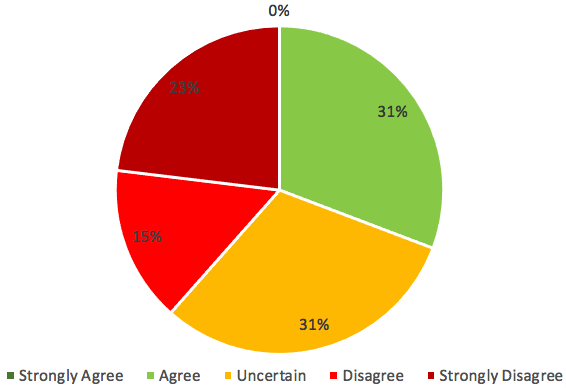

Question 2: Recent data shows UK house sellers are putting up prices despite rate rises and the cost of living crisis. Do you agree that a house market crash is imminent?

Any comment on this question?

Edmund Cannon: I agree. House prices need to be much lower. Crashing the housing market is not the best way to get to that end goal. I think that the Bank of England will finally take the step to raise interest rates and hence have said “agree”, but this depends on the Bank. There is some justice in calling the governor “failing Bailey” – he has made a lot of mistakes – even just this week.

Anonymous: I’m uncertain. House prices being the main indicator of economic success for politicians in the UK, and houses being the main financial assets, politicians have incentives to sustain the bubble as much as they can. That being said, this is a bubble and the high interest rates might crash it.

Richard Davies: I strongly disagree. No – this is wishful thinking from would be buyers and headline-seeking journalists. Britons will cut other things before they go into arrears on their mortgages, and people simply will not sell below the price at which they bought. It is a misnomer that 2008 was about house prices in the UK – draw the chart and you will see that it was not (it was about commercial property) – and household balance sheets are stronger now than they were then.

Sarah Smith: I agree. I just don’t see how house prices can continue to rise as the affordability of mortgage repayments falls – although the stamp duty cuts may delay the inevitable for a short while.

Verdict: Fewer economists in this survey agree than disagree that a UK house-price correction is imminent. According to Richard Davies, house prices are in line with fundamentals and it is disingenuous to say otherwise. Edmund and Sarah are on the other side of the argument – but neither hold this view ‘strongly’. For Edmund, house prices will only come down if the Bank of England commits to further rate hikes, whereas for Sarah, stamp duty cuts may resemble a temporary lifeline during the cost of living crisis. Almost a third of respondents are neither way inclined; one economist cites too much political uncertainty.

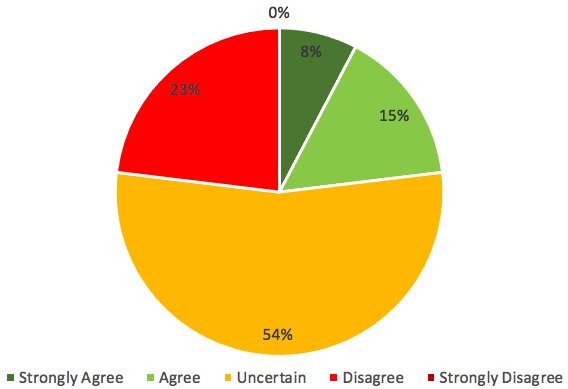

Question 3: The Economist estimates the US government is on the hook for liabilities worth more than 6 times its GDP; growing faster than output. Do you agree this is of major concern?

Any comment on this question?

Edmund Cannon: I’m uncertain. Without knowing the US government’s assets, this question is meaningless.

Anonymous: I’m uncertain. It depends on the market confidence in future fiscal policies, thus it depends on the next president.

Richard Davies: I’m uncertain. Debt at 600% of GDP is highly unlikely to me – I’d query that figure.

Sarah Smith: I disagree. Although markets are volatile, the US is in a very different position to the UK – not least with the dollar as a reserve currency.

Verdict: Regarding the graph from the top of this page, the majority of surveyed economists are unsure what to conclude. Several respondents take issue with the underlying methodology and so question the validity of the results. Alternatively, one economist is uncertain because of so many unknowns in America’s political trajectory. Although just under half of respondents agree or strongly agree that the graph elicits major concern, they give no comment to back up their views. A further quarter of economists disagree with the statement; Sarah says the strength of the greenback is reason enough to be optimistic.

One entry in this blog series from two years ago asked a similar question, but focused on UK public sector debt instead of the US. Back then, most surveyed economists felt better placed to say they were not concerned; there was also a much lower proportion of ‘uncertain’ replies. Ignoring the different size and location of the sample (and also ignoring the different macroeconomic environment today compared to 2020), perhaps economists are more troubled by public sector debt levels in the US than in the UK. Still, I have suggested before that economists living in Bristol may simply feel more inclined to chime in on developments within the country they are based.

Final thoughts: uncertainty goes academia

When it comes to the three questions in this survey, it seems academics are just as uncertain as financial markets right now. The exception was the topic of recession, for which most economists agree with recent remarks from the Bank of England. Consenus-building was strongest here. But on the potential of an imminent UK house-market crash, there was an almost equal split of those saying yes, no, and maybe. It proved even more difficult to find consensus in question three, which had double the proportion of ‘uncertain’ responses than question one, as well as the comparatively lowest proportion of ‘strongly’ held views.

But a few times in the survey, several interpretations were made of the same question. On such occasions, economists found themselves talking over each other as they disagreed over different topics entirely. This is an obstacle to consensus-building. If vague questions prompt equally vague responses (such was the case for the third question), it becomes hard to distinguish confusion from disagreement, or consensus from clarity…

What would you like to Ask the Experts? Send an email to Ethan at xn19143@bristol.ac.uk with your suggestions for future questions on this blog.

With special thanks to Dr Hans Sievertsen and Professor Sarah Smith.

Discover research from the School of Economics on our website.