The second in the ‘ask the expert’ series, Economics student, Ethan Lester asks academics and department staff for their views on current economic issues.

The second in the ‘ask the expert’ series, Economics student, Ethan Lester asks academics and department staff for their views on current economic issues.

Staff at the University of Bristol’s School of Economics grapple with COVID19-related economic questions. Where does the expert consensus lie?

As the public health crisis unfolds, so too does the economic crisis. Can the experts agree on how to solve it? Recent evidence would generally answer in the affirmative: economists can and do agree with each other on key issues. Indeed, among the IGM panel of leading academic economists from the world’s top universities, only 8% of experts are expected to go against the grain on topical economic questions, and for nearly a third of these questions, there are no dissenting voices at all (Discover Economics: Covid19: The Expert Economist View).

In the spirit of the IGM panel, this series on the Economics Blog aims to locate the consensus among Bristol University staff on some of the main economic questions raised by COVID-19. As was explained in the series introduction, the format entails three questions to be answered on a scale of agreement (a ‘likert scale’), with the option to add a comment.

Economic circumstances are constantly changing, to the extent that questions put to the experts may find themselves ‘outdated’ by the time they are published. Indeed, the second question in this edition considers a quote which assumes the abrupt and immediate end of any employment protection scheme for UK workers by October 31st – we now know this to not be the case, following a recent announcement by Chancellor Sunak.

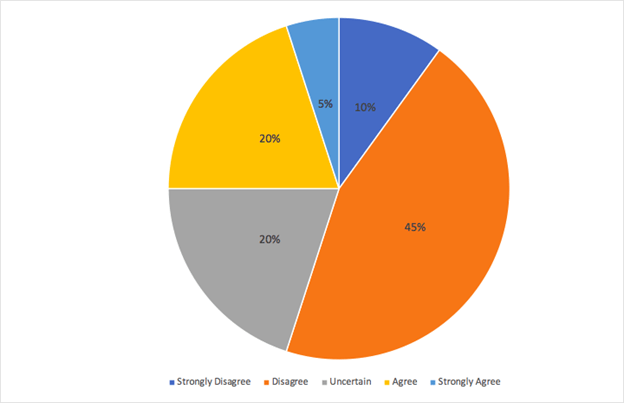

Question 1: The Bank of England recently discussed implementing ‘negative policy rates’, which would be a first in the Bank of England’s 326-year history. Do you agree that negative interest rates would be the right move now?

20 responses

Any comments on this question?

Anonymous: I strongly disagree. Evidence of the effectiveness of negative interest rates is unclear at best. At this point in time, the economy’s weakness lay elsewhere. Lower interest rates may not do anything.

Edmund Cannon: I disagree. I am not convinced that monetary policy has much ability to stimulate aggregate demand. Cutting lower interest rates from where they are now risks greater imbalances in the housing market and irreparable damage to what remains of the UK pension system.

Anonymous: I agree. Cutting interest rates is a standard policy response to recession.

Hans H. Sievertsen: I disagree. Lower interest rates is a normal reaction to a recession, but we are not in a normal situation. It is not clear to me that access to funds (business/mortgages) is the key problem for the economy right now, but even if it is a key problem, other policy tools might be more effective.

Jahir Islam: I’m uncertain. Under the current economic climate, a negative interest rate may do very little for economic recovery. Which segments of the economy are they targeting – mortgage, business borrowing (investment vs working capital), consumption loan, savings? How long can this negative interest rate be sustained? Is the economy (or significant part of it) liquidity constrained? We can analyse each of these segments and may fail to see any significant impact of negative interest rate on them.

Anonymous: I disagree. Low interest rates are creating a bubble in the financial markets.

Ahmed Pirzada: I agree. With furlough scheme rolled, both COVID and Brexit related uncertainty increasing, inflation on the lower side and banking system reasonably stable, the Bank of England should be open to the possibility of negative rates even if the evidence on their effectiveness is so far mixed.

Verdict: Since nominal negative interest rates have never before been set by the central bank in the UK – and only very rarely by the central banks of other economies – the experts are generally quite sceptical that it would ever work. 55% of respondents either disagree or disagree strongly with interest rates being depressed below a level which is already at historic lows. Some economists argue this move would cause instability in financial markets, while others doubt the strength of the link between interest rates and economic growth. One economist alludes to ‘other’ responses in the monetary policy toolkit, perhaps referring to the Quantitative Easing programme the Bank relaunched in June for the first time since the global financial crisis. As for the 25% of experts in the ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’ camp, textbook examples were given for why lowering interest rates could help to, for example, tackle worryingly low inflation levels or boost consumer spending in anticipation of Brexit uncertainty. Overall, only some economists believe negative interest rates would have the same positive effects that reduced (yet positive) interest rates do.

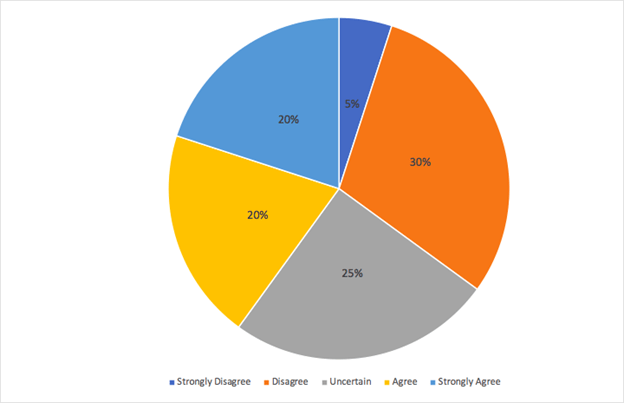

Question 2: The Trades Union Congress forecasts a ‘tsunami’ of unemployment for when the Job Retention Scheme ends on October 31st. Do you agree that the Chancellor should consider a general extension of the scheme?

20 responses

Any comments on this question?

Edmund Cannon: I disagree. Although coming up with a sector-specific scheme also has dangers, it would be unwise to prop up sectors that have no long-run future. For example, given that environmental reasons mean that we need to curtail international air travel by a huge margin, we may as well close down much of the aviation sector now: the money would be better spent re-training workers for different completely different jobs.

Anonymous: I’m uncertain. The scheme should be extended for businesses which cannot operate due to social distancing. It is uncertain whether the scheme should be extended for businesses which in principle can operate even during social distancing, but suffer e.g. from low demand.

Jahir Islam: I disagree. Extension of the scheme might not be sustainable. It would be better to offer direct help to the businesses so that they can keep their business running as much as possible, so that they can avoid redundancy.

Conrad Copeland: I strongly agree. Instituting lockdowns and restrictions (even local ones) without support for people and businesses will strangle the economy and make recovery that much harder. It would be far better to institute universal relief for everyone (not just workers, as the furlough scheme did). This would allow people to weather the crisis and create a situation in which spending and employment can bounce back after the restrictions are lifted, ideally allowing businesses to retain the workers they already have. Once workers are unemployed, it’s much harder to restart the economy since you will have a lag as hiring and job matching takes place.

Steven Proud: I strongly agree. The scarring effect of (early) unemployment is well known, and could significantly impact on individuals’ life chances. However, there’s no guarantee that demand will spring back when COVID eventually is dealt with, so the scheme might need to also be about creating mobility.

Ahmed Pirzada: I agree. The government should have waited for the future outlook to have become more certain before gradually rolling back the Job Retention Scheme. It is important to allow old jobs to be replaced by new jobs as the structure of the economy changes in response to COVID/Brexit. But the cost of this transition will be more bearable once uncertainty decreases and outlook improves.

Verdict: Our experts struggled to find much common ground on this question, as illustrated by the fairly evenly distributed pie chart above. Those who disagreed have qualms with who should be covered by the Job Retention Scheme: should the government be overly concerned with keeping workers in dying industries (ones that cannot cope with the new age of socially distanced commerce, or the transition towards green energy)? And perhaps fiscal safety nets ought only to be continued for employers, but not employees? But if this is the case, should all employers be recipients of the scheme when some are more in need of financial help than others? Answers by economists who agree with an extension were less focused on these alternative, more ‘targeted’ proposed versions of the Job Retention Scheme. Overall, while the exact shape of the Job Retention Scheme proves highly controversial among our experts, none of them want to see the total discontinuation of the Scheme without its replacement by a more narrow, perhaps refined, version of it.

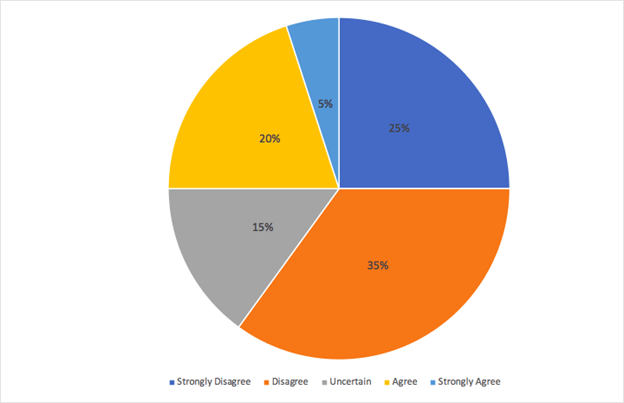

Question 3: UK public sector debt now exceeds 100% of GDP for the first time since 1960. Do you agree that this is a serious cause for concern right now?

20 responses

20 responses

Any comments on this question?

Anonymous: I agree. The COVID contribution to this is not the problem, the problem is that governments are leaving a huge debt to younger cohorts in terms of government debt, environmental issues, and future pensions. The balance of political power, leaning towards the elderly, explains this situation.

Edmund Cannon: I strongly disagree. It is not an immediate problem (it will be a problem later).

Anonymous: I strongly agree. Although it is a serious concern, it may also be the right thing to do. Classical theory of optimal debt issuance prescribes that temporary shocks to fiscal expenditures should be spread over a longer time period with debt.

Conrad Copeland: I’m uncertain. Debt exceeding GDP in itself is not necessarily a problem. The issue is what the money is spent on and who holds it. The problem for the UK arises in the fact that much of the money has been wasted on half-measures and poorly targeted relief that is, perversely, causing both economic harm and public health harm. Debt in this crisis is expected, but it would be far better to spend the money on schemes that actually support people and businesses in a consistent way that will allow them to withstand the pressures the crisis is bringing and let them bounce back after the crisis is over.

Hans H. Sievertsen: I disagree. Debt in itself is not a concern (in the short run), especially because we know that a source for this is COVID19. However, ineffective (and expensive) policies and structural spending discrepancies are a concern.

Ahmed Pirzada: I disagree. The yield curve has shifted downwards compared to last year. The market is not concerned about rising debt levels. As long as the government remains committed to fiscal discipline in future, the rise in debt levels today should not hold the government back from supporting the economy.

Verdict: Seeing as only a quarter of responses are ‘agree’ or ‘strongly agree’, there is quite a clear consensus among our experts that news of rising public sector debt isn’t (at least currently) too problematic. The frequent justification given by our experts who hold this view is that public sector debt has only ballooned for the short term, and that so long as governments are allocating funds appropriately, higher debt today will pay for itself with the economic recovery tomorrow. What should be a concern, some of the experts say, is that if governments amass debt before even beginning to address the climate crisis, the younger generation will be greatly overburdened by public sector debt.

Final thoughts: uncertainty over COVIDnomics

We continue to find ourselves in uncharted economic territory, with policies which hold no precedent in economic history. Negative interest rates and a jobs retention scheme might have been pie in the sky economics prior to COVID-19, but these uncertain times have truly shifted the Overton Window. Without an extensive literature on the effectiveness of these novel policies, it should come as no surprise that ‘uncertain’ was the second most commonly given response by our experts to both Question 1 and Question 2. Question 3 does have historical precedent (sovereign debt exceeded 100% in 1960), so maybe this is why ‘uncertain’ was only the fourth most common response. Notably, Question 3 provided the clearest cut consensus in this month’s survey.

However, historical polls conducted with Chicago Booth’s IGM panel have indicated that economists only rarely hold their views with a high degree of certainty, even before the pandemic. The uncertainty over Questions 1 and 2 might not, then, owe itself to the novelty of the policies under discussion, but to how broad these questions were.