Staff at the University of Bristol’s department of Economics grapple with some COVID19-related economic questions. Where does the expert consensus lie?

Staff at the University of Bristol’s department of Economics grapple with some COVID19-related economic questions. Where does the expert consensus lie?

Asking the experts: in a new series for the economics blog, Economics undergraduate student, Ethan Lester puts COVID19-related economic questions to department staff and writes up their responses.

Looking for consensus in economics

There is a famous adage that if 10 economists were put in a room, they would come to 11 different conclusions. How fair is it to say this, really? For over a decade, the Initiative on Global Markets (IGM) Forum at Chicago Booth Business School has asked leading economists for their views on topical issues, allowing us to see whether they find any common ground. The initiative conducts weekly polls of its Economics Experts Panel, consisting of around 50 US and European academic economists from the world’s most established universities. These economists are asked for their views on topics ranging from climate change, to immigration, to minimum wage and to Brexit. All IGM poll questions are answered using the Likert scale: the options are Strongly Agree, Agree, Uncertain, Disagree, and Strongly Disagree. Participants must also indicate a confidence level in their response (on a scale of 1 to 10). They have the option to provide a free-form comment to explain their selection.

The New York Times has praised the IGM polls for providing ‘an easily digested summary of the insights of mainstream economics into continuing political controversies’. This article aims to emulate the IGM’s successful format and presentation. Currently the most pressing economic questions are about the impact of COVID19 on the economy. These are the questions we have decided to put to the University’s Economics staff.

The IGM Panel has been heralded for its ideological and geographical diversity, but the reality looks quite different, and is indicative of certain discipline-wide disparities which one might associate more with STEM subjects. 80% of the US panel, for instance, obtained their PHDs from just five institutions (92% of which are US-based); while only 1 in 5 panelists identify as female.

Regrettably, some of these systemic biases have filtered into our survey. Female representation from our respondents might be marginally higher than the makeup of the European and US IGM Panels, but this figure is still a meagre 24%. We must be mindful of facts like these if we are to ever achieve true diversity of thought and analysis in economics.

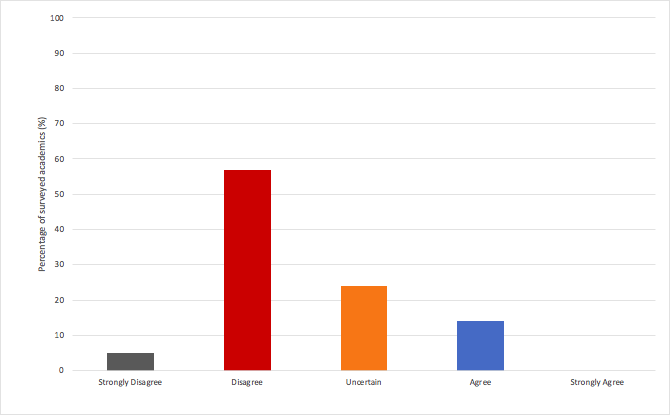

Question 1: Do you agree with Andy Haldane (Bank of England Chief Economist) that the UK economy is on track for a V-shaped recovery?

21 responses. On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being most confident), the average respondent’s confidence was 6.52.

Any comment on this question?

Anonymous: I’m uncertain. I think Haldane’s record is poor (he is vastly over-rated: as head of the unit dealing with financial instability his record up to the financial crisis of 2008 speaks for itself), but he has access to more data than me.

Steven Proud: I disagree. The period of recovery is likely to be tempered by two major issues: Firstly, ongoing social distancing measures (which may lead to increased pressure on firms), and secondly, destruction of productive capital that may already have taken place.

Anonymous: I disagree. I think a lot of sectors are going to find business as usual hard; consumers are cautious; we still don’t know how many people on furlough are going to lose their jobs. Overall, there is too much uncertainty to expect bouncing back.

Hans Henrik Sievertsen: I disagree. It is always difficult to predict future economic activity, but in this case it is extraordinarily difficult. We both have the COVID19 pandemic and Brexit. I therefore find it brave to guess about the shape of the recovery. However, given the job loss, the reduction in spending, and that some sort of social distance measures likely will be in place for a while I doubt that the recovery will be v-shaped.

Gerard van den Berg: I disagree. A hard Brexit is looming. Even if Brexit is only moderately hard, it will cause further trouble. Next, the public health care system has not been reformed and is therefore unable to deal smartly with local outbreaks except by imposing further massive interruptions.

Ahmed Pirzada: I’m uncertain. Data does point to a relatively quick recovery than what was expected earlier. But what remains to be seen is how the economy will behave once governments in the UK and elsewhere start withdrawing the support they have extended so far (e.g. furlough scheme and loan guarantees). The hope is that businesses will start earning enough to pay back any new loans they have taken during this period.

Verdict: 62% of the economists surveyed either disagreed or strongly disagreed with the Bank of England’s Chief Economist. Notably, Brexit was only factored into 6 of the economists’ analysis; while the significance of a potential ‘second wave’ of Coronavirus was only considered by two respondents. To the economists, recovery is going to depend on factors like the continuation of furlough and business support, in conjunction with the outlook for consumer confidence. That there may remain structural, longer-term impacts of the pandemic to be seen suggests an immediate economic rebound is wishful thinking. Think less ‘V-shape’, and more ‘Nike tick’.

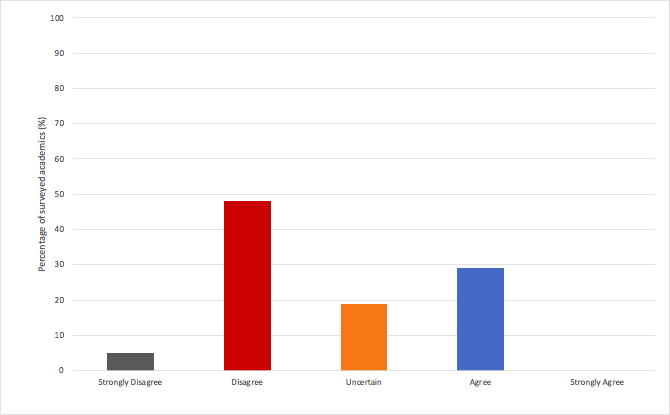

Question 2: Have furlough schemes now made some kind of Universal Basic Income (UBI) more likely?

21 responses. On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being most confident), the average respondent’s confidence was 6.76.

Any comment on this question?

Edmund Cannon: I’m uncertain. This is a political question and I am an economist.

Steven Proud: I disagree. This is much more of a normative question, and will be addressed through political views. In my opinion, the current political establishment is unlikely to support UBI.

Jahir Islam: I’m uncertain. This commitment may not get the priority in the near future, given the fiscal deficit and business climate that will persist in coming years.

Conrad Copeland: I agree. UBI has been brought to the forefront of the political-policy discussion, but I’m not certain that the political will of the major parties has shifted significantly.

Anonymous: I agree. The peculiarity of the Universal Basic Income is that it is unconditional. The furlough scheme instead remains conditional. So, social insurance may be more generous in the future, but policy makers may still opt for schemes with a degree of conditionality.

Anonymous: I disagree. Furlough is closer to the unemployment insurance (paid to workers who do not work) rather than to UBI (paid to all unconditionally).

Anonymous: I agree. The pandemic and the resulting economic uncertainty has provided a strong case for Universal Basic Income.

Verdict: Especially interesting about this question is that, while some economists found a UBI beyond the remit of economic discussion altogether, others provided confident analyses. The contentious nature of this question therefore yields little consensus: almost equal numbers of economists ‘disagree’ as those who do not. However, there was some agreement on the view that furlough schemes have shifted the Overton window somewhat and that the realm of possibility for economic relief policy has expanded since the introduction of employee furlough.

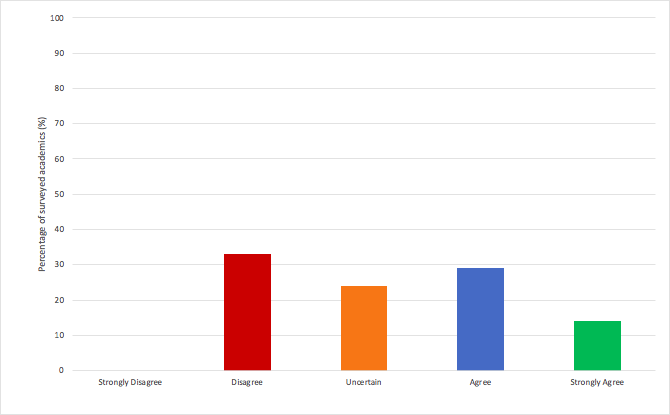

Question 3: The global pandemic will hit some universities’ finances hard. Should the government commit to bailing them out if they need help?

21 responses. On a scale of 1 to 10 (10 being most confident), the average respondent’s confidence was 7.48.

Any comment on this question?

Steven Proud: I’m uncertain. This is a two-edged sword. On the one hand, Universities are important for the economy, as drivers of innovation, educators, and in supporting intellectual curiosity, but on the other hand, a guarantee of a bailout creates moral hazard – VCs might just decide to spend money profligately, if they have the guarantee of being bailed out if they go under.

Julia Wirtz: I’m uncertain. The government should sustain universities in their role to provide education and as cultural institutions. Higher education/research is one of the very few internationally competitive sectors in the UK. I am not sure there is public interest to support profit-driven institutions with an excessive management and marketing overhead and vanity building projects.

Anonymous: I disagree. Recent IFS report suggests that the unis at risk are largely the “bottom tail” in terms of quality. Letting a uni fail is hard because of the impact on local economies and also on students who are part way through their studies. Yes, higher education has positive externalities but I would prefer to see money spent on non-uni options which are under-funded in the UK.

Conrad Copeland: I agree. Failing to bail out universities will force them to seek increased attendance (particularly international students) in order to make up the funding shortfall (as we have started to see some do), this will make containing Covid-19 in the upcoming academic year more difficult.

Hans Henrik Sievertsen: I’m uncertain. There are positive externalities of higher education which calls for a Gov’t intervention. However, if being at risk is correlated with low quality/poor management, it is unclear that the Gov’t should intervene and create a moral hazard situation. Money might be “better” spent in other areas, for example investment in school children who suffered an (unequal) learning loss.

Anonymous: I disagree. A bail-out should be on the table and this possibility should be transparently communicated to universities. However, I don’t think at this point there is a need to commit to bail. Unlike banks, a bankruptcy of a single university is unlikely to lead to systemic risk. Commitment to bail encourages moral hazard in university management. Finally, the UK government has already huge fiscal obligations due to pandemic, so at this point it is uncertain to me whether additional obligation would not threaten the soundness of public finances. Consider e.g. Ireland which went into fiscal trouble because it took over toxic debt from its banks. I don’t think bailing out UK universities would be anywhere near as costly and bailing out Irish banks, but fiscal space available to the UK government at this point is also much different.

Ahmed Pirzada: I agree. It should depend on whether the effect on any given university is temporary or permanent. If temporary, then the government should provide support just like the government is providing support to the rest of the economy. But if permanent, then it really depends on to what extent the university is contributing towards improving social welfare (e.g. research and teaching excellence). Otherwise, resources should be allowed to move towards more productive activities.

Verdict: This question polarised views more than the previous two – almost equal numbers of economists ‘agreed’ and ‘disagreed’, and, on average, opinions were held more confidently (including the only ‘strongly agree’ response in the entire survey). And where the economists ‘agree’ that governments should commit to bail-outs, there is little consensus within this camp as to how exactly relief funds should be allocated. Lessons learnt from the bail-out of financial institutions in 2008 are highlighted by the economists, including problems such as moral-hazard, systemic risk, and a bloated budget deficit.