BSc Philosophy and Economics student, Charlotte explores coronavirus and inequality, looking at what this means for education in her Economics of Coronavirus blog.

BSc Philosophy and Economics student, Charlotte explores coronavirus and inequality, looking at what this means for education in her Economics of Coronavirus blog.

Charlotte wrote her blog in response to our student competition earlier this year, where we invited students to write their own Economics of Coronavirus blog exploring any aspect of the Covid-19 pandemic.

Coronavirus and inequality: What does it all mean for education? By Charlotte Collier

The coronavirus pandemic is the biggest economic shock our generation has experienced, the integration of the global economy meaning the impacts are prevalent. With pandemics of this scale being so rare, it is difficult to predict how significantly the effects will be felt. With the virus being described as the ‘great leveler’ messages of solidarity and selflessness have been widespread. But schools are taking different approaches to operating in lockdown. To what extent will all students be affected in the same way?

What is the relationship between COVID-19 and inequality?

The relationship between pandemics and inequality has been long established. There is a relationship of interdependency between inequality and pandemics, where both exacerbate each other. This can be described as a ‘feedback loop’ (Fisher and Bubola, 2020). This means that the virus is more likely to worsen inequality, but the existence of inequality worsens the spread of the virus. Therefore, those who are less economically well off in a society are more likely to be affected by the virus, experiencing more profound adverse effects than high earners.

Historical pandemic examples demonstrate this relationship. After the 2009 UK influenza pandemic, the World Bank suggested that mortality rates in the poorer parts of England were 3 times higher than in affluent areas (Mamelund, 2017). Additionally, the highest mortality rates during the Spanish Flu pandemic were among the working classes, those living in small flats, and in poorer areas (ibid). With the world more globalised than ever, and the pandemic being the most large scale economic shock we have witnessed in our lifetimes, the impacts of COVID-19 are likely to be more severe than any pandemics of the past. Economists have already predicted a more severe economic downturn than what we experienced in 2008 (Giles, 2020).

Inequality, therefore, is likely to be increased to a greater extent than what has been seen in past pandemics. As we experience social lockdown, those on low incomes are likely to struggle. Lowest earners are 7 times more likely to work in job sectors which have been shut down, such as retail, hospitality, arts and leisure. With the majority of lower earners’ spending being on necessities, such as rent and groceries, without a source of income they will struggle to source their basic needs (BBC Sounds, 2020). High income earners are also more likely to be able to work from home, being able to afford the technology required to do so. Those on low incomes are therefore more likely to be exposed to contracting the virus. They are also more likely to live in more densely populated living spaces like tower blocks, or to be working in essential roles (ibid). ‘Pre-existing vulnerabilities only get worse following a disaster’, emphasized Nicole A. Errett, a public health expert at the University of Washington (Fisher and Bubola, 2020). These impacts have been widely discussed, but the inequality caused by cyclical unemployment might not be the largest concern. Differences in education might have long-term implications and could be one of the most harmful consequences.

How has education been impacted by COVID-19 for people from different backgrounds?

A year 12 student at Forest School in East London described her school routine as having changed very little, still following her regular timetable online. She described the £6585 per term school as even setting slightly more homework than usual, receiving daily contact with her teachers. The difference in quality of education since remote schooling seems stark, with just two percent of state schools using live video conferencing, compared to 28% of private schools (Cohen, 2020).

Whilst quality of schooling is a significant factor in education, ‘one of the biggest problems facing British schools is the divide between rich and poor, and the enormous disparity in children’s home backgrounds and the social and cultural capacity they bring to the educational table’ (Benn and Millar, 2006). This is prevalent in the distinction between education in different households. The Forest School pupil, whose parents both have higher education qualifications, including an M.D said, ‘my mum can directly help me with any help needed in biology and my dad is able to help me with history as a result of his interest and knowledge as well as his law degree’. Not only is direct help a factor, but understanding of a productive homeworking environment also makes a difference, with the Forest pupil describing it as ‘fairly easy to get on with work without family members distracting me’. Comparing this to some state schools, where 40% of students do not have access to a device for home working, income and home environment proves to be significant in children’s ability to learn (ibid). Some children are continuing a regular school day, whilst some who are from more deprived backgrounds are doing no learning during lockdown.

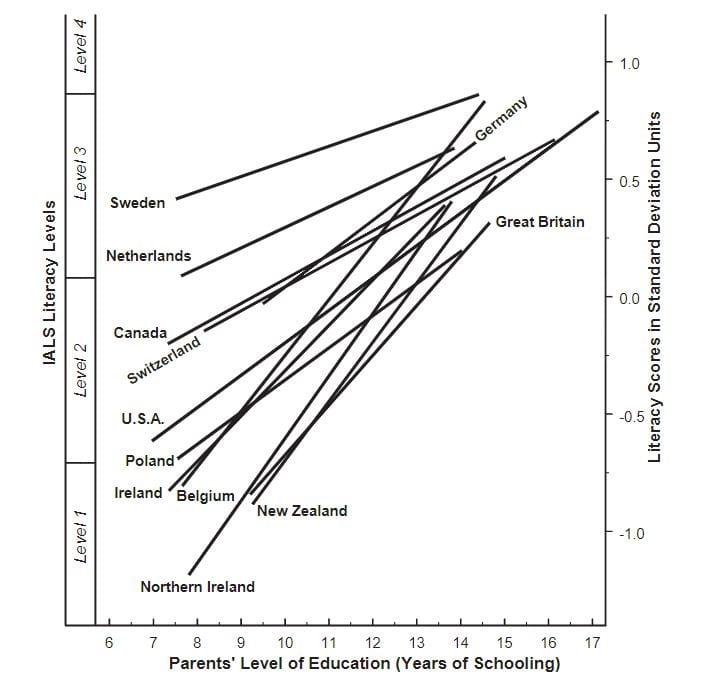

‘Education is generally thought of as the main engine of social mobility in modern democracies’, social mobility being the ability of an individual to move up and down the income ladder. The graph below, taken from Willms’s paper, shows that there is a strong correlation between parents’ education and their child’s literacy score in an international, standardized test (Willms, 2003). Within each country, the more years of schooling a parent has, the better their child’s score. The literacy scores between each country converge with higher levels of parental education, but are extremely different for fewer years of schooling. Generally, more equal economies had better levels of attainment, with the lowest score in Sweden being level 3. Less equal economies like the UK had steeper social gradients, the lowest score being level 1, indicating there is a greater inequality in literacy levels which is dependent on parents’ ability.

Figure 1: Children’s literacy levels and Parents’ Level of Education

This information highlights the importance of maintaining a strong education system through lockdown and the following period of recovery. With education levels and income being strongly correlated, these differences in education quality are likely to exacerbate income inequality in the future.

What might these differences mean for the future?

Increased income inequality is a matter of concern because of its social consequences. Income inequality is closely related to increased crime rates, higher numbers of imprisoned criminals, teenage pregnancy, mental illness, obesity, lower status of women and many other factors leading to a reduced quality of life. The increased inequality in society is detrimental because people will be worse-off, unhappier and unhealthier than they might otherwise be.

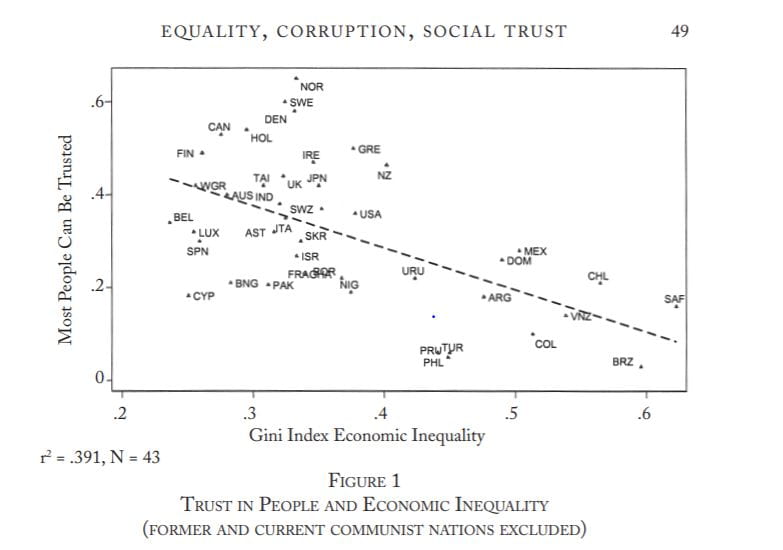

It is crucial that individuals comply with government advice and rules about social distancing to limit these impacts. However, particularly in the early weeks of social distancing and lockdown, there was confusion and skepticism about social distancing rules. Whilst this was partly due to a lack of clarity in rules, this could have been exacerbated by lack of trust. The model below is part of a six-equation model estimated by Uslaner, showing a correlation between trust in people against income inequality (Rothstein and Ulsaner, 2005). The correlation shows that generally, the higher the level of inequality in an economy, the fewer people can be trusted. The r2 value indicates a closeness of fit of data to the regression line (the line of best fit). A value of 0.391 shows whilst there is some deviation from the trend, there is a clear negative linear relationship between trust and inequality in an economy.

Figure 2: Trust in people and economic inequality

‘In low-trust societies with high degrees of economic inequality, universal programs are likely to fail for lack of political support’ (Rothstein and Ulsaner, 2005). Dramatic social change has been seen due to the coronavirus, and the reluctance to comply with social distancing rules at the beginning of pandemic could be due to lack of trust in government and others, correlated with the UK’s high level of inequality. “The single best predictor of social trust and virtually every type of participation is education” (Ulsaner, 2002). If these theories are correct, the lack of trust and cooperation in low income households could be related to inequality in education. The increased inequality caused by the pandemic could be further increased due to lack of trust and compliance in government action, potentially another reason why low income households are more susceptible to catching the virus.

Economics is discipline saturated with statistics, models and numbers, but we need to deconstruct these and remember that economics is a social science about people, and we need to do more to make people better off. Whilst coronavirus has been described as a ‘great leveler’, it is clear that the opposite is the case. Attitudes of selflessness and solidarity have increased though. Hopefully these attitudes will remain after the pandemic settles and we will recognise the need to do more to make a more equal society and a stronger society which is more resilient to future shocks to the economy. To do so, we need to find methods to improve quality of education in low income households and reduce inequality.

Bibliography:

BBC Sounds, 2020. The Inequalities Of Lockdown. [podcast] The Briefing Room. Available at: <https://www.bbc.co.uk/sounds/play/m000h0w0> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Benn, M. and Millar, F., 2006. A Comprehensive Future: Quality And Equality For All Our Children. London: Compass, p.145.

Cohen, T., 2020. Coronavirus: Working-class children less likely to take part in lockdown school lessons. Sky News, [online] Available at: <https://news.sky.com/story/coronavirus-how-lockdown-is-affecting-learning-for-working-class-pupils-11975696> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Fisher, M. and Bubola, E., 2020. As Coronavirus Deepens Inequality, Inequality Worsens Its Spread. The New York Times, [online] Available at: <https://www.nytimes.com/2020/03/15/world/europe/coronavirus-inequality.html> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Giles, C., 2020. Britain heading for a deep recession, say experts. Financial Times, [online] Available at: <https://www.ft.com/content/8ccae8d2-6eb0-11ea-89df-41bea055720b> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Mamelund, S., 2017. Social inequality – a forgotten forgotten factor in pandemic influenza preparedness. Tidsskriftet, [online] Available at: <http://file:///C:/Users/charl/Downloads/Tidsskrnorlegeforen.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Rothstein, B. and Ulsaner, E., 2005. All for All: Equality, Corruption, and Social Trust. World Politics, [online] 58(1), pp.41-72. Available at: <https://projects.iq.harvard.edu/gov2126/files/rothstein_2005.pdf> [Accessed 30 April 2020].

Ulsaner, E., 2002. The Moral Foundation Of Trust. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press.

Willms, J., 2003. Literacy proficiency of youth: evidence of converging socioeconomic gradients. International Journal of Educational Research, [online] 30, pp.247-251. Available at: <https://reader.elsevier.com/reader/sd/pii/S0883035504000278?token=6CE6B96682035DC047E07F0CC42C3B479D5CB825C1F9B6436E09E4494E0368982742FEA834342F8D358CE62D993DD56E> [Accessed 30 April 2020].